Land Near Millbeck Hall Cottage, Millbeck, Keswick, Cumbria: Archaeological Topographic Survey, Watching Brief, and Excavation

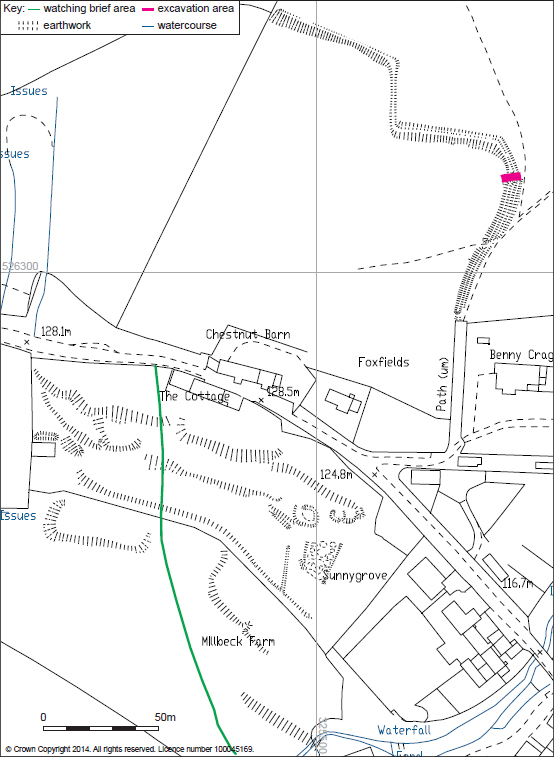

Following the submission of a planning application for the creation of a hydroelectric scheme on land near Millbeck Hall Cottage, Millbeck, Keswick, Cumbria, a condition was placed on the planning consent requiring archaeological remains be taken into consideration as per the recommendations of an environmental statement. Following discussions with the Archaeology and Heritage Service at the Lake District National Park a request was made for an archaeological desk-based assessment and walkover survey, for the route in order to assess the archaeological impact of the scheme. This was carried out by Greenlane Archaeology in December 2014 and January 2015 and identified two areas of earthworks, most likely associated with the medieval settlement of Millbeck, that would be affected (https://greenlanearchaeology.co.uk/?projects=land-near-millbeck-hall-cottage-millbeck) and following this a programme of archaeological topographic survey, watching brief, and excavation was agreed in order to mitigate its effects. This work was carried out between March and April 2015.

The hamlet of Millbeck is first recorded in 1260, although the place-name evidence suggests a Norse presence in the early medieval period and there are numerous prehistoric sites from the wider area. The history of the wider Skiddaw massif becomes dominated by the mining industry from the medieval period onwards, but in Millbeck the textile industry was particularly dominant throughout the 19th century.

The topographic survey recorded a large bank and ditch feature on the north side of the road and a series of linear earthworks, terraces and other features to the south. The form of the bank and ditch is similar to other medieval boundary earthworks, comprising a wide earth bank topped with orthostatic boulders with a parallel ditch, and while the sharp bend in it is similar to recorded deer park boundaries, where the bend created a ‘funnel’ to control the movement of animals. It is most likely to represent the ‘head-dyke’ that divided the cultivated land from the open fell beyond. The terraces in the southern area most likely represent cultivation platforms, although some could have housed buildings, and there is some phasing evident within these and the other earthworks that relates largely to post-medieval developments. Two circular features are probably the potash kilns previously identified by Mike Davies-Shiel, although these seem to been cutting into the terraces and so are presumably later.

The watching brief revealed deep deposits of subsoil in the area of the southern earthworks, as well as two pieces of medieval pottery, which might indicate the date at which the terraces originated, although later finds were also made. A single possible shallow linear feature was also identified, but this might relate to a small area of ridge and furrow located nearby.

The excavation targeted a section of the bank and ditch that would be cut through by the pipe trench. This revealed the bank to be constructed from gravelly clay, probably that derived from the excavation of the ditch, edged with orthostatic boulders. The ditch had been apparently deliberately backfilled, probably in the 19th century when the whole boundary had ceased to be significant and a track was cut across it.

The work at Millbeck has allowed a detailed record to be made of a range of features that provide considerable information relating to the medieval settlement. The pottery finds demonstrate archaeologically for the first time the presence of settlement in the area during the 12th – 14th centuries, and probably provide a date for the terraces in the southern area. The excavation across the head-dyke is potentially the first time such an investigation has been carried out in Cumbria and provided useful information about the structure of a monument of this type, and although it was not possible to date it archaeologically it is likely to also be medieval and had clearly gone out of use by the 19th century.

The full report will be made available on the Archaeology Data Service website.